All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Perioperative Hemodynamic Changes During Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Decortication for empyema

Abstract

Background and Objective:

Hemodynamic consequences during video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with decortication during empyema drainage are unclear. The aim of the study was to assess the perioperative hemodynamic changes decortication during empyema drainage.

Methods:

A prospective study enrolled 23 patients with empyema who underwent decortication. Hemodynamic parameters were continuously obtained at 15 time points: supine two lung ventilation after induction, lateral decubitus position and two lung ventilation, lateral decubitus position and one-lung ventilation, every 5 min after decortication upto 60 minutes and at the end of surgery. We divided patients into three groups according to microorganisms, group 1: patients with no growth of organism; group 2: patients with staphylococcus aureus and pseudomonas; group 3: patients with streptococcus, yeast and fungus, gram-positive bacilli, and mycobacterium tuberculosis. The hemodynamic variables were recorded by the third-generation Vigileo/FloTracTM system and variables for each time interval were compared with the baseline by Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test.

Results:

In group 1, hemodynamic parameters showed no significant changes over time. However, in group 2 and 3, both CO and CI increased 10 to 15 minutes after decortication and remained elevated during the remainder of surgery. However, SVR and SVRI decreased 10 to 15 minutes after decortication in both groups, especially, with a more significant decrease noted in group 2 than group 3.

Conclusion:

Close perioperative hemodynamic monitoring during decortication in empyema patients is required because of potential hemodynamic disturbances especially patients with toxic microorganisms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Thoracic empyema is an inflammatory process related to collection of pus between the visceral and parietal pleural layers, often a complication of pneumonia, surgery, iatrogenic procedure, or chest trauma [1-5]. Treatment for an empyema consists of antibiotics and early drainage [6]. Except in its earliest phase, chest tube drainage alone rarely provides adequate therapy. Pleural decortication is necessary for patients with pleural loculations. This is accomplished by removing the fine peel on the lung, draining the infected fluid, and allowing the underlying lung to expand. Recently, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) for the decortication procedure has been a minimally invasive alternative which provides reduced morbidity, postoperative pain, and hospital stay [7-9].

General anesthesia with one-lung ventilation (OLV) using a double-lumen endobronchial tube is needed during VATS decortication. One lung ventilation (OLV) is performed routinely during thoracic surgery. Some of the consequences with the technique of endobronchial intubation are associated with OLV. A marked decrease in arterial oxygenation is the consequence of nonventilated and collapse lung. Hypoxia during OLV may be caused by inhibition of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction which can lead to increase pulmonary vascular resistance [10, 11]. OLV superimposed by the inflammatory process of empyema, likely to carry a high risk of hemodynamic changes. Close hemodynamic monitoring using invasive devices (arterial lines, central venous catheter, etc) during the decortication procedure is essential for patients with empyema. However, report on hemodynamic evaluation for patients undergoing surgery for treatment of empyema is still lacking.

Recently, less invasive techniques have become available for hemodynamic parameter monitoring. The Vigileo/FloTracTM system (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) provides continuous monitoring that uses arterial pressure waveform analysis to estimate cardiac output (CO) and other hemodynamic parameters [12-14]. In a previous study demonstrated that second generation of FloTrac software underestimates CO than the transpulmonary thermodilution using (PiCCO plusR, Pulsion Medical Systems, Munich, Germany) in septic patients [15]. The new third-generation FloTrac software was developed from a human database containing many recordings from septic and liver transplant patients who were often vasodilated. In a recent multicenter study investigate the accuracy of the third-generation software in patients with sepsis, particularly patients with low total systemic vascular resistance which is concerned in second-generation software [16]. In this study, they demonstrated that precision and accuracy of third-generation FloTrac software are as good as that of PAC thermodilution in critically ill patients. Therefore, the aim of this study is to assess the hemodynamic changes during VATS decortication for patients with empyema using the third-generation Vigileo /FloTracTM system.

2. METHODS

This study was evaluated and approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from patients undergoing VATS for empyema decortication.

2.1. Patients

Twenty-five patients with empyema who underwent VATs for treatment of empyema from January to December 2016 were studied. Exclusion criteria included patients younger than 20 years, documented coronary disease, valvular heart disease, and use of any inotropic or vasopressor drugs before surgery. The diagnosis of empyema was made using clinical presentation (such as cough, dyspnea, fever, leukocytosis, and chest pain); radiographic studies include anteroposterior and lateral chest radiographs which demonstrate parenchymal infiltrate or consolidations, and pleural space fluid; chest computed tomography (CT) scan which show fluid density collection in the pleural space、thicken pleural and pus-like thick purulent pleural fluid obtained by thoracentesis.

2.2. Anesthetic Management

General anesthesia was induced with fentanyl (4–10 μg/kg) and propofol (0.5–1.5 mg/kg). Cisatracurium (0.1–0.2 mg/kg) was given to facilitate orotracheal intubation. After induction of anesthesia, a left-sided, double-lumen endobronchial tube (Bronchocath, Mallinckrodt, Athlone, Ireland) of appropriate size was placed and its correct position was confirmed by auscultation and eventually by bronchoscopy. Anesthesia was maintained with 2–3% sevoflurane with a 1.0–1.3 minimal alveolar concentration level. Mechanical ventilation with 100% oxygen was started with tidal volumes of 10 ml/kg and an initial respiratory rate of 9–10 breaths/min. During OLV, tidal volumes were reduced to 6–8 ml/kg to maintain peak inspiratory pressures < 35 cm H2O, and the respiratory rate was increased to avoid respiratory acidosis. A radial arterial pressure line was placed contralateral to the operated hemithorax. We placed a central venous catheter into the right internal jugular vein. Then, the artery catheter and central venous catheter were connected to the Vigileo/FloTracTM system. Patient data (age, gender, body weight, and height) were entered later. While the check of arterial line and central venous pressure waveform fidelity was done, the Vigileo/FloTracTM system was zeroed and hemodynamic parameter measurement initiated.

2.3. Study Protocol and Data Collection

The first measurement of hemodynamic variables was performed immediately after induction of anesthesia and insertion of a central venous catheter and an arterial pressure line. The hemodynamic variables, including mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), mean pulmonary arterial pressure (MPAP), CO, cardiac index (CI), stroke volume (SV), stroke volume index (SVI), systemic vascular resistance (SVR), systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), stroke volume variation (SVV), and central venous pressure (CVP) were recorded by the Vigileo/FloTracTM system. Those hemodynamic variables were obtained at various time points: T0 (supine two lung ventilation after induction); T1 (lateral decubitus position and two lung ventilation); T2 (lateral decubitus position and 5 min after OLV); T3–T14 (every 5 min after decortication begins up to 60 min); and T15 (end of surgery).

The following data were collected for each patient: age, sex, body weight, comorbidities, causes of empyema, hemodynamic changes during decortication, pathogens isolated from cultures of the pleural fluid, duration of ICU and hospital stays, postoperative infection, and mortality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data were entered into a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and statistically analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Troy, NY, USA). Preoperative and postoperative variables were assessed using descriptive statistics for the mean and standard deviation of continuous variables and frequency tables for categorical variables. Hemodynamic variables for each time interval were compared with the baseline by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. P < 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

3. RESULTS

The study included twenty five patients who had undergone elective or emergent decortication surgery. We excluded two patients because they needed a vasopressor to maintain stable hemodynamics during decortication. Therefore, twenty three patients were enrolled for analysis. The demographic data of study patients are shown in Table (1). The mean age and body weight of the patients were 55.8 ± 19.1 years and 63 ± 13.9 kg, respectively. There were 17 male patients (73%) and six female patients (26%). Most of the patients received elective surgery (65%) and the remaining 35% received emergent surgery. The most frequent comorbidities noted was essential hypertension (52%) and diabetes mellitus (21%). The empyema was associated with pneumonia in the majority of cases (91%) and with surgery in the remaining 2 patients.

| Variables | Cases (n=23) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.8 ± 19.1 |

| Body weight (kg) | 63 ± 13.9 |

| BMI | 24 ± 4.8 |

| Gentle (male) | 17 (73%) |

| Recent surgery | 8 (35%) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 11 (52%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (21%) |

| COPD | 1 (4.3%) |

| CVA | 2 (8.7%) |

| Malignancy | 7 (30%) |

| Timing of surgery | |

| Emergency | 8 (35%) |

| Elective | 15(65%) |

| Preoperative | |

| Hb (mg/dl) | 12.5 ± 1.1 |

| Hct | 34.5± 1.3 |

| CRP | 143± 30.8 |

| Causes of empyema | |

| Parapneumonic | 21 (91%) |

| Post-surgery | 2 (8.7%) |

Table (2) displays the perioperative and postoperative variables of the study patients. Mean arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) after induction was 333.2 ± 27.05 mmHg which dropped to 207.4 ± 34.3 mmHg 15 min after OLV. 65% of the patients were extubated within 24 h and two patients were extubated more than 72 h. Most of the patients (73%) stayed in ICU for less than 3 days and six patients (26%) stayed more than 3 days. For hospital stays, 11 patients (48%) were discharged from hospital within 14 days and 12 patients (52%) stayed more than 14 days. Overall, there were three deaths, a mortality rate of 13%. One patient died within 7 days and the other two were hospitalized for more than 30 days. Overwhelming sepsis was the cause of death in these patients. Pleural fluid was obtained from all patients and analyzed for organisms. Seven of the patients (30%) showed no growth at the time of decortication. The organisms identified included Staphylococcus aureus (three patients, 13%), Pseudomonas (three patients, 13%), Streptococcus (three patients, 13%), yeast and fungus (two patients, 8.7%), Gram-positive bacilli (two patients, 8.7%), and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (three patients, 13%).

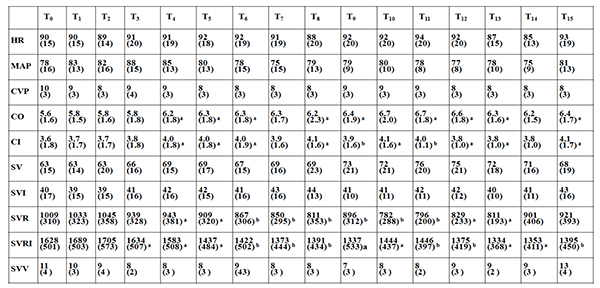

Table (3) displays the average hemodynamic data at the defined time intervals. CO and CI were significantly increased 10 to 15 min after decortication and remained increased for the whole procedure compared to baseline T0 . Importantly, SVR and SVRI were significantly decreased 10 to 15 min after decortication and remained decreased for the whole procedure compared to baseline T0 . However, no significant effects on HR, MAP, CVP, SV, SVI and SVV were observed during the whole procedure.

| Variables | Cases (n=23) |

|---|---|

| Arterial blood gas analysis | |

| After induction | |

| pH | 7.40 ± 0.12 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 40.03 ± 1.03 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 333.2 ± 27.05 |

| HCO3− | 25.3 ± 0.92 |

| 15 minutes after one lung ventilation | |

| pH | 7.34 ± 0.18 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 46.2 ± 1.77 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 207.4 ± 34.3 |

| HCO3− | 25.6 ± 0.73 |

| Intraoperative Hb (mg/dl) | 11.0 ± 0.46 |

| Extubation | |

| OR | 3 (13%) |

| < 24 hr | 15 (65%) |

| > 24 hr < 48 hr | 3 (13%) |

| > 72 hr | 2 (8.7%) |

| ICU stays | |

| < 3 days | 17 (73%) |

| > 3 days | 6 (26%) |

| Hospital stays | |

| < 14 days | 11 (48%) |

| > 14 days | 12 (52%) |

| Mortality | |

| Alive | 20 (87%) |

| Death | 3 (13%) |

| Postoperative infection | |

| No | 20 (87%) |

| Yes | 3 (13%) |

| Bacteriological profile | |

| Sterile (no growth of organism) | 7 (30%) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3(13%) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3(13%) |

| Gram positive bacilli | 2(8.7%) |

| Streptococcus groups | 3(13%) |

| Yeast and fungus | 2(8.7%) |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 3(13%) |

We then divided patients into three groups according to microorganisms from pleural aspirate and observed the perioperative hemodynamic data. Those with no growth of organism at the time of decortication were defined as group 1, patients with Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas organisms were defined as group 2, and patients with Streptococcus, yeast and fungus, Gram-positive bacilli, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis were defined as group 3. Fig. (1) displays the hemodynamic data including CO, CI, SVR, and SVRI at the defined time intervals in the three groups. In group 1, CO, CI, SVR, and SVRI remained stable throughout the procedure. However, in groups 2 and 3, both CO and CI increased 10 to 15 min after decortication and remained increased for the whole procedure compared to baseline T0. However, SVR and SVRI decreased 10 to 15 min after decortication compared to baseline T0 in both groups; in particular they were more significantly decreased in group 2.

4. DISCUSSION

This observational study describes hemodynamic responses to decortication for empyema patients, evaluated using a Vigileo/FloTracTM system. Empyema is one of the oldest of diseases and is associated with considerable morbidity and a high mortality rate more than 10% [6]. With early diagnosis and antibiotic therapy of pneumonia, uncomplicated and simple parapneumonic effusion do not generally progress to empyema. However, in some patients, parapneumonic effusion becomes more complicated and leads to empyema [17]. The organizational stage of empyema requires surgical intervention, which usually takes the form of decortication [18].

|

Decortication is a surgical procedure in which the fibrous wall of the empyema cavity, the cortex, rind, or peel, is stripped of the adjacent visceral and parietal pleura along with the evacuation of pus, blood clots, and fibrin material from the pleural cavity. This eliminates the pleural sepsis and allows the underlying lung to expand [19, 20]. This is accompanied by an increased risk of hemodynamic disturbance. VATS with decortication has shown reliably good outcomes in the management of pleural empyema in several series in recent decades [21, 22]. However, its routine use is out of reach for most hospitals because it carries an obvious operative risk and morbidity.

VATS with decortication is performed under general anesthesia and OLV. Mostly, to achieve OLV a double-lumen bronchial tube is used and allows the lung to collapse passively. Alteration in pulmonary gas exchange during OLV has been investigated in a clinical trial. Although a marked decrease in arterial oxygenation is the consequence of a nonventilated and collapsed lung, a study demonstrated that hemodynamic variables during OLV remained stable through the procedure [10]. In our study, during OLV, we also found that hemodynamic variables remained stable before decortication. However, the hemodynamic consequences of decortication in empyema patients are to a great extent unknown. Furthermore, no conclusive recommendations exist as to which kind of hemodynamic monitoring should be preferred in the situation. Therefore, we studied the hemodynamic changes during decortication in empyema patients under OLV in order to derive recommendations for the application of hemodynamic monitoring in this specific perioperative situation. Evidence supports that a large amount of toxic materials and cytokines accumulate in pleural fluid [23, 24]. During decortication, these toxic materials and cytokines enter the blood stream which leads to hemodynamic changes. The relationship between cytokines and hemodynamic instability has been extensively studied. A study showed an association between increased levels of TNF-α and decreased systemic vascular resistance and left ventricular stroke work index [25]. These hemodynamic changes were thought to be mediated by nitric oxide release secondary to increased cytokine levels [26, 27]. A study demonstrated that a patient given an interleukin-2 (IL-2) infusion showed a 63.4% decrease in systemic vascular index [28]. This is confirmed in our study, as SVR and SVRI decreased significantly 10–15 min after the beginning of decortication and remained decreased for the whole procedure. In our study, we excluded 2 of the study patients. CO increased in these patients, however, SVR and SVRI decreased very low and inability to maintain blood pressure. They received vasopressor for blood pressure restoration during the procedure. Persistence hypotension, along with the presence of hypoperfusion abnormalities may lead to organ dysfunction and mortality. Therefore, closed perioperative hemodynamic monitoring throughout the procedure is required in these patients because of potential hemodynamic disturbance.

Microorganisms of various classifications have the capability of establishing different hemodynamic response. In our present study, we demonstrated that for group 2 microorganisms including the aerobic Gram-negative bacillus Pseudomonas and Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, SVR and SVRI were decreased more significantly than in groups 1 and 3. In the aerobic Gram-negative bacillus Pseudomonas, lipopolysaccharides are an essential component of the outer membrane. Studies in animal models and in human volunteers have documented that this cell wall component is the biologic equivalent of an “endotoxin,” producing inflammatory and hemodynamic profiles associated with Gram-negative bacterial sepsis and septic shock [29]. In the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, cell components have been identified and these appear to be biologically equivalent to endotoxins in stimulating the inflammatory response from host cells associated with sepsis and septic shock. The peptidoglycan layer outside the cell membrane of Gram-positive bacteria as well as non-peptidoglycan polymers, the teichoic acids, have been shown to stimulate the release of cytokines, specifically tumor necrosis factor and IL-1 [30]. The release of endotoxins, exotoxins, and cytokines from pleural fluid into the circulation appears to be a major mechanism by which bacteria can cause hemodynamic instability during decortication. This interplay of endotoxins and exotoxins with vessel endothelium results in vasodilatation, a decrease in vasomotor tone. A possible mediator of this vasodilatation may be the nitric oxides, possibly of endothelial cell origin but also of macrophage origin, induced by the interaction of endotoxins or exotoxins on these cells. This was evidenced in our study by significantly decreased SVR and SVRI in patients with group 2 microorganisms.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that decortication in empyema patients was associated with decreased in SVR and SVRI throughout the procedure. Careful monitoring throughout the procedure is required because of potential hemodynamic disturbances especially in toxic microorganisms. The Vigileo/ FloTracTM system is minimally invasive and easy to set up and use. Moreover, precision of third-generation FloTrac software has been preserved and accuracy has been improved. This minimally invasive device designed to measure hemodynamic parameters may be considered to further improve hemodynamic control and outcomes in decortication for empyema patients.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Applicable: approved by the Ethics Institutional Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, and written informed consent was obtained from patients.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.