All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The GlideScope Video Laryngoscope: A Narrative Review

Abstract

The GlideScope video laryngoscope has had a profound impact on clinical airway management by virtue of providing a glottic view superior to direct laryngoscopy. Since its introduction circa 2003, hundreds of studies have attested to its value in making clinical airway management easier and safer. This review will update the reader on the art and science of using the GlideScope videolaryngoscope in a variety of clinical settings and its relation to other airway management products. Topics covered include GlideScope design considerations, general usage tips, use in obese patients, use in pediatric patients, use as an adjunct to fiberoptic intubation, and other matters. Complications associated with the GlideScope are also discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

For many individuals, the advent of modern airway management begins with Miller’s straight-blade laryngoscope [1], which is itself an improvement over earlier developments [2]. The curved laryngoscope blade in common use today, designed to fit into the vallecula and lift the epiglottis anteriorly, was first introduced around 70 years ago [3]. Since that time, considerable thought has gone into establishing the optimal design and use of laryngoscopes [4-9].

The advent of technical methods to go beyond traditional line-of-sight laryngoscopic techniques led to a variety of optical and rigid fiberoptic designs (e.g., Bullard, Airtraq) [10] and later, electronic devices to facilitate laryngoscopy (videolaryngoscopes). Developments in videolaryngoscopy have been reviewed by numerous authorities [11-17].

Descriptions of the early use of the GlideScope videolaryngoscope have been provided by a number of authors [18-24]. Subsequently, an overwhelming number of publications on the design and use of the GlideScope (GS) and other videolaryngoscopes have been published, as noted in some of the above cited reviews. This review aims to update the reader with respect to the art and science of the GlideScope videolaryngoscope, its relation to other airway management products and it application to various clinical scenarios. Out of necessity, we have specifically not reviewed other videolaryngoscope designs except if they are related to the GlideScope in comparative studies.

2. GLIDESCOPE DESIGN

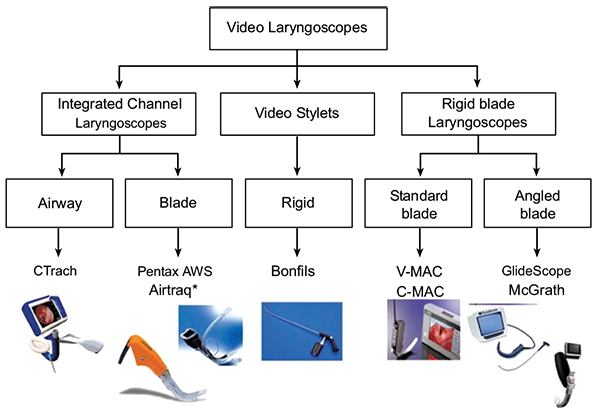

Healy et al. have provided a taxonomy of videolaryngoscope designs that helps one understand the design of the GS in relation to other videolaryngoscope designs [16] (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 and Table 1 illustrates the various members of the GS family of airway products. The reusable GS designs utilize a high-resolution microminiature video camera embedded into a plastic laryngoscope blade. A second design uses a transparent disposable blade that fits over a long thin “video baton”. The blades are angled at 60 degrees up from the horizontal. The main advantage of the version utilizing disposable blades is that the GS can be made available for reuse in a mere few seconds, eliminating the logistical difficulties of disinfection between uses (simply swap out the blade), while the reusable unit requires high-level disinfection between uses, a process that makes the GS otherwise unavailable. (Detailed cleaning instructions are available at the manufacturer's Web site.)

From: Healy DW, Maties O, Hovord D, Kheterpal S. A systematic review of the role of videolaryngoscopy in successful orotracheal intubation. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012 Dec 14;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-32. PubMed PMID: 23241277; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3562270.

Copyright ©2012 Healy et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. From an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

|

GVL 2: Patient weight: 1.8 - 10 kg Blade length (tip to handle): 47 mm Thickness (height) at camera: 14.5 mm Width at camera: 18 mm |

GVL 4: Patient weight: 40 kg – Morbidly Obese Blade length (tip to handle): 102 mm Thickness (height) at camera: 14 mm Width at camera: 27 mm |

|

GVL 3: Patient weight: 10 kg - Adult Blade length (tip to handle): 82 mm Thickness (height) at camera: 14.5 mm Width at camera: 20 mm |

GVL 5: Patient weight: 40 kg – Morbidly Obese Blade length (tip to handle): 102 mm Thickness (height) at camera: 14 mm Width at camera: 27 mm |

Two later GS designs consist of a reusable unit (AVL Reusable) that is available in 4 sizes (GVL 2,3,4,5) as well as a version featuring disposable blades (AVL Single Use) that is available in 6 sizes (AVL 0, 1, 2, 2.5, 3, 4) in association with two sizes of video batons. Both units feature an HDMI output for optional connection to external monitors, a built-in educational tutorial to familiarize users with the unit, and a USB port where recorded videos can be saved onto a flash drive.

The latest GS products are made from titanium and are available in two models. The first is a low-profile hyper-angulated blade, available in two sizes, while the second uses a more traditional Macintosh blade, also available in two sizes. Both designs offer full-color imaging, with LED illumination as well as anti-fog technology. Four models of single-use video laryngoscopes are also available.

3. GLIDESCOPE USE

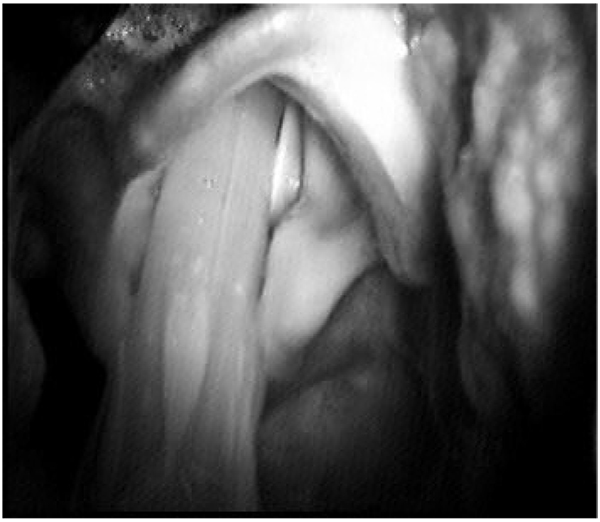

The curved blade shape of the GlideScope is simple to place, and users quickly feel comfortable inserting the device and distracting the tongue and jaw, in a manner similar to direct laryngoscopy. Users should use the GS like a regular Macintosh laryngoscope with the exception that they should intubate with the head in the neutral position and that they should watch the LCD display monitor instead of looking directly only after the ETT is placed into the oropharynx (see discussion on complications). Note that the image provided by the GlideScope Fig. (3) is looking upward toward the larynx from within the hypopharynx, and consequently is not dependent on patient head-neck position. A neutral position (face plane parallel to the ceiling) allows more oropharyngeal space compared to atlanto-occipital extension, which narrows the hypopharyngeal space.

As a rule, few difficulties are encountered in obtaining an adequate view in the few seconds it takes most users to learn to manipulate the GS. In some cases, the view is improved with posterior displacement of the trachea, but in most cases, this maneuver is not helpful (see discussion on usage tips). The fact that several individuals can simultaneously witness the intubation on the LCD display is of enormous teaching value and can be clinically valuable in difficult cases where significant pathology is found. The GS works fairly well in the presence of blood and secretions (a consequence of the protected camera position on the blade) but the presence of vomitus, hemoptysis or hematemesis can impair the view; in such cases, it is wise to suction the oropharynx thoroughly prior to insertion.

Many users find that the principal limitation in using the GS is not in getting a good view of the glottis, but rather in manipulating the endotracheal tube (ETT) through the vocal cords. Using an ordinary ETT without a stylet results in a floppy ETT that is very hard to direct through the cords, and successful placement almost always requires some form of stylet, such as a Mallinckrodt Satin-Slip® Intubating Stylet, or the GlideRite Stylet Fig. (4) in order to avoid the ETT from ending up in an excessively posterior position.

Studies showing the GS to be easier to use than DL are numerous. For example, Healy et al. [16] compared the Glidescope, CMAC, and Storz DCI with the Macintosh laryngoscope during simulated manikin difficult laryngoscopy; all three of the methods of video laryngoscopy studied were found to be superior to the Macintosh laryngoscope Fig. (5). This issue is discussed in more detail in a later section.

From: Healy DW, Picton P, Morris M, Turner C. Comparison of the Glidescope, CMAC, storz DCI with the Macintosh laryngoscope during simulated difficult laryngoscopy: a manikin study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012 Jun 21;12:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-11. PubMed PMID: 22720884; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3519500.

Copyright ©2012 Healy et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. From an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

4. USAGE TIPS

Experience shows that the principal limitation in using the GS is not in getting a good view of the glottis, but rather in manipulating the tracheal tube through the vocal cords. Successful tracheal tube placement is usually best achieved by using a stylet formed in the shape of a ‘hockey stick’ (with a 90° bend) to help ensure that the tube is directed sufficiently anteriorly to enter the glottis Fig. (4). Once the tube enters the glottis, it is can also be helpful to withdraw the stylet by about 3 cm, followed by advancing the tube slightly, so as to avoid it hitting against the tracheal wall [23].

Walls et al. [25] described a patient where extreme difficulty in using the GlideScope occurred despite a CL grade 1 laryngoscopic view because “the trachea formed a steep posterior angle with the laryngeal/glottic axis” with the ETT tip consequently becoming stuck against the anterior tracheal wall. Successful intubation was ultimately achieved by rotating the ETT 180 degrees, thereby redirecting the ETT posteriorly.

Corda et al. [26] found that a jaw thrust maneuver was often helpful in improving the glottic view when the GlideScope is used, but that no significant improvement was noted with cricoid pressure. They “recommend the use of jaw thrust as a first-line maneuver to aid in glottic visualization and tracheal intubation during GlideScope videolaryngoscopy.”

Table 2 provides additional tips. Other potentially helpful suggestions have been offered by other GlideScope experts [27-39].

| 1. Use the device for most easy / routine cases until you are very comfortable with its use. That way, when you need it for a particularly difficult airway case you will already be quite familiar with the mechanics of the device. In one study [140], primary intubation with the device was successful in 98 percent of 1,755 cases and rescued failed direct laryngoscopy in 94 percent of 239 cases. |

| 2. When placing the GlideScope, insert it slightly to the left of the midline to ensure adequate room to the right of the device to get the tube into the mouth. This is particularly important when large diameter tubes are inserted, such as the double lumen tubes used for thoracic surgery or the wide-diameter tubes with embedded electrodes used in many thyroid surgery cases. |

| 3. When placing the endotracheal tube, start by placing it gently under direct vision and then switch to the monitor view once it is has been gently placed deep into the oropharynx. This two-phase approach is recommended to reduce the chance of causing harm or injury to one of the tonsillar pillars or to the soft palate. |

| 4. The angulation of the tip of the endotracheal tube is very important. Too little a bend, and the endotracheal tube tip points to the esophagus and not the glottic aperture; too much of a bend and the endotracheal tube tip tends to get caught on the anterior tracheal wall. A reusable rigid stylet that matches the angulation of the blade is available; it has been shown to be equal in efficacy to a disposable malleable stylet. |

| 5. It is not uncommon that videolaryngoscopy users achieve an excellent view of the glottis but experience difficulty advancing the endotracheal tube into the glottic aperture because of the tube abutting against the anterior tracheal wall. If this happens, withdrawing the stylet by 3 to 5 cm tends to straighten the tip of the tube and propel it in the right direction. Other techniques, such as the “gear stick” technique [30], the “reverse loading” technique [31] or the “J-shape” technique [29] also can be helpful. |

| 6. Paradoxically, maximizing the size of the glottic view with full and complete advancement of the GlideScope into the oropharynx may adversely impact on the ease of intubation. With more limited advancing of the laryngoscope, the “approach angle” of the endotracheal tube is often more amenable to easy passage of the tube into the glottis. That is, the position that provides the best glottic view is generally not the position that makes intubation the easiest, where a “good enough” view is usually the most favorable [141]. Where a suboptimal view is obtained, use of an airway introducer can sometimes be helpful. These include the Eschmann guide [142, 143] the Frova introducer [144] as well as other products. |

| 7. Nasal intubations are surprisingly easy. No stylet is used. Manipulate (flex or extend) the head to ensure easy passage of the tube. Forceps are rarely needed. However, use of regular Magill forceps is difficult in this setting; rather, use a pair of curved intubating forceps should the need arise. |

| 8. Using the GlideScope for awake intubation can be valuable when fiberoptic scopes are unavailable. It is accomplished after the patient's airway has first been well anesthetized with lidocaine or other drug. |

| 9. Remember that the GlideScope can be useful in swapping out endotracheal tubes [145]. |

| 10. Finally, remember that there are situations where the video laryngoscope will fail you, and that these are often unexpected. Always have a backup plan for this eventuality. For me, this usually involves asleep fiberoptic intubation, asleep fiberoptic intubation in conjunction with the GlideScope (as described above), insertion of a supraglottic airway followed by use of a 4 mm fiberscope jacketed by an Aintree catheter, or simply waking up the patient. |

5. ENDOTROL TUBES

The Endotrol-tracheal tube has a control that allows the tube tip to be positioned to a more anterior position. Imagining that this feature might be helpful for intubation using the GS, Cattano et al. [40] conducted a study in which two of the study arms compared the GS used in conjunction with the Endotrol ETT (but employing no stylet) against the GS using a GlideRite-styletted standard ETT. The authors concluded that “the Endotrol ETT, as compared to a standard ETT with a non-malleable stylet, is associated with longer intubation times and a subjective increase in difficulty of use.”

6. PREDICTION OF DIFFICULT GS INTUBATION

While the GS generally provides a superior glottic view compared to DL, predictive features specific to difficult GS intubation have not been identified to the extent that they have for DL. Tremblay et al. [41] recorded demographic and morphometric factors for 400 patients undergoing tracheal intubation. After induction, DL was performed to determine the Cormack / Lehane grade of glottic visualization [42, 43], followed by intubation using the GS. After their data analysis, the only predictors of difficulty with GS intubation (e.g., multiple attempts) turned out to be high Cormack / Lehane grades during direct laryngoscopy, a high upper lip bite test score [44] and a short sternothyroid distance. Of these, only the last two, of course, can be assessed at the bedside.

Adnet's intubation difficulty scale (IDS) [45] has been used extensively as a metric to define difficult intubation and to compare methods of intubation. For example, Yousef et al. [46] used the IDS to compare the GlideScope, the LMA CTrach™ and direct laryngoscopy in a population of 90 obese patients. The authors found that “easy, moderately difficult, and difficult tracheal intubation as defined by the intubation difficulty score (0, 1-5, and >5) were met in 12, 11, and 7 patients of the DL group, respectively, while, tracheal intubation was easy in (29, 28 patients) and moderately difficult in only (1, 2 patients) in the GVL and CT groups, respectively. The authors concluded that “the GlideScope videolaryngoscope improved intubation time for tracheal intubation with less upper airway morbidity compared with the LMACTrach and Macintosh direct laryngoscope.”

However, a study by McElwain et al. [47] found that the correlation between the IDS score and both user rated difficulty and the time needed for tracheal intubation was significantly stronger for the Macintosh laryngoscope than for the indirect laryngoscopes studied (GlideScope, Pentax AWS, Airtraq). These findings led the authors to conclude that the IDS “performs less well with indirect laryngoscopes than with the Macintosh laryngoscope” and that clinicians should use “caution with the use of this score with indirect laryngoscopes.”

7. FORCE AND PRESSURE DISTRIBUTION

Because forces applied to airway soft tissues by direct laryngoscopy may cause injury as well as an endocrine stress response, a number of investigators have studied the forces applied during laryngoscopy and intubation.

Hirabayashi et al. [48] considered the possibility that a reduction in forces applied during GS laryngoscopy might result in reduced anterior airway anatomy distortion, providing a possible explanation of the perception that nasotracheal intubation with the GS is easier than when DL is used. To study this hypothesis that authors studied 20 patients in a protocol where each patient underwent laryngoscopy using both the GS and DL with Macintosh blade. During each laryngoscopy, a radiograph was taken when the best view of the larynx was obtained, and these radiographs were then studied for anterior airway distortion and cervical spine movement. The distance between the epiglottis and the posterior pharyngeal wall during GS use was found to be reduced by 21% as compared to Macintosh laryngoscopy. The authors concluded that “both anterior airway distortion and cervical spine movement during laryngeal visualization” were reduced for with use of the GS.

Russell et al. [49] compared the forces used with the Macintosh laryngoscope vs. the GlideScope in 24 adult patients using three FlexiForce pressure sensors attached along the concave surface of each blade. Compared with the Macintosh laryngoscope, the authors found lower median peak force (9 N vs 20 N), average force (5 N vs 11 N) and impulse force (98 N vs 150 N) with the GlideScope. Methodological comments on this study have been provided by Pieters et al. [50]. A similar study using manikins has been published by the same team [51]. Carassiti et al. [52] similarly compared the Macintosh laryngoscope vs. the GlideScope in a study of 30 adult patients using film pressure transducers. They found that the force applied using the GlideScope was much lower than with the Macintosh (8 N vs. 40 N on average). They also noted that when using the Macintosh laryngoscope, forces were concentrated mostly on the tip, whereas the GlideScope “distributes the forces more homogeneously to the tissue”, reducing the potential for injury. An earlier manikin study of similar design was published by Carassiti et al. [53]. Methodological comments on this last study have been provided by Fiadjoe and Stricker [54].

8. GLIDESCOPE USE IN OBESE PATIENTS

Mask ventilation as well as intubation can be difficult in morbidly obese patients. These patients are also at increased risk of hypoxemia during tracheal intubation [55-57]. Consequently, a number of studies have examined whether the GlideScope might be helpful in such cases.[REMOVED HYPERLINK FIELD]

Andersen et al. [58] compared GS intubation with the Macintosh direct laryngoscope (DL) in a group of 100 consecutive morbidly obese patients. The authors found that “laryngoscopic views were better in group GS with Cormack-Lehane grades 1/2/3/4 distributed as 35/13/2/0 vs. 23/13/10/4 in group DL” and also found that better IDS scores with use of the GS. However, intubation times were longer in the GS than in the DL group (average of 48 s vs 32 s), although the authors noted that that the “increased intubation time was of no clinical consequence as no patients became hypoxemic.”

A study by Ydemann et al. [59] compared the GS with the Fastrach (FT) in intubating 100 obese patients. Average GS intubation time was 49 s, with 61 s using the FT, a difference that was not statistically significant. The authors experienced one esophageal intubation using the GS and six when using the FT. Although the authors wrote that the GS and the FT should be “considered to be equally good when intubating morbidly obese patients” the possibility that the study was underpowered to detect any differences between the two techniques should also be considered.

Motivated by concerns about delayed gastric emptying in obese patients, a study by Gupta and Rusin [60] compared rapid-sequence GS intubation in patients induced in the semi-erect position with rapid-sequence GS intubation in the standard supine position. Although “no differences were observed in the intubation parameters or patient safety” desaturation episodes occurred 50% less frequently in the semi-erect group, a finding that did not reach statistical significance.

A study of 150 obese patients by Maassen et al. [61] compared the GlideScope Ranger, Storz V-Mac, and McGrath Series 5 videolaryngoscopes against DL in a cross-over study design. All 3 videolaryngoscopes provided an equal or better view of the glottis as compared to DL. The authors found that the number of attempts necessary to intubate the trachea differed significantly among the devices (average 2.6 attempts for the GS, 1.4 for the Storz, and 2.9 for the McGrath). The average intubation times were 33 s for the GS, 17 s for the Storz, and 41 s for the McGrath VLS. The authors concluded that that Storz V-Mac “had a better overall satisfaction score (and) intubation time” and required a “reduced number of intubation attempts” compared to the other devices tested. One possible criticism of this study was the use of a “very stringent” definition of an intubation attempt, as “each approach of the ETT to the glottic entrance, even without complete withdrawal of the ETT out of the mouth” counted as an attempt. A more serious criticism is that a rigid stylet was employed only “if intubation was not feasible after 2 intubation attempts” despite that fact that routine use of a stylet is recommended by the manufacturers of both the GS and the McGrath devices.

A study by Abdelmalak et al. [62] compared GS intubation with flexible fibreoptic intubation in 75 obese patients randomly assigned to one of these two intubation methods following the induction of general anesthesia. Although it was hypothesized that tracheal intubation with the GlideScope would be advantageous compared with flexible fibreoptic intubation, no significant differences were found for the time needed to intubate, the difficulty of intubation, the success rate for the first attempt, the number of attempts, the incidence of hypoxemia, the amount of post-intubation bleeding and the incidence of sore throat. While the authors concluded that “for experienced users, the time required to intubate the trachea in anaesthetised obese patients is similar with the GlideScope and a flexible bronchoscope” the much steeper learning curve associated with use of flexible fibreoptic intubation as compared to intubation using the GS suggests that these findings likely apply only to clinicians very experienced with flexible fibreoptic intubation.

Finally, Yumul et al. [63] compared three different VL devices (Video-Mac, GlideScope, and McGrath) against DL in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery and found that all three VL devices studied provided improved glottic views compared to DL (p < 0.05).

9. USE OF THE GLIDESCOPE FOR EMERGENCY AIRWAY MANAGEMENT OUTSIDE OF THE OPERATING ROOM

In recent years the GlideScope has taken on a special role in managing airway emergencies outside of the Operating Room, such as in the emergency department, ICU or in the prehospital setting. One particularly interesting issue concern the question of whether videolaryngoscopy should be the first choice for tracheal intubation in managing emergency airways in such settings.

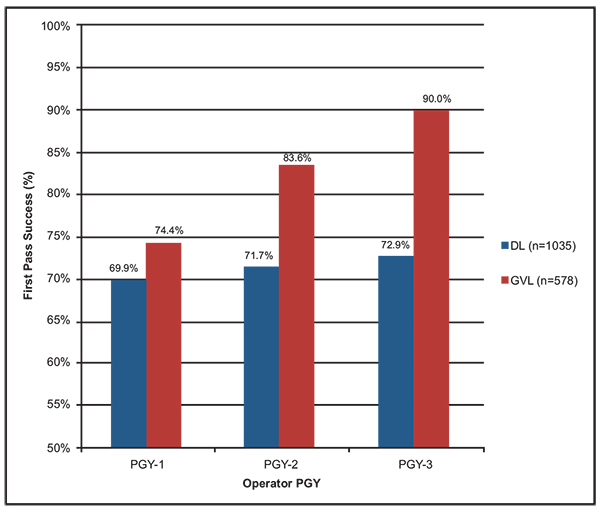

Sakles et al. [64] compared resident performance for direct laryngoscopy versus the GlideScope over the course of emergency medicine residency training and found that while there was no significant improvement over time in first pass success with direct laryngoscopy, there was “substantial improvement” with use of the GlideScope Fig. (6). In another study by Sakles et al. [65] the authors compared the incidence of esophageal intubation when emergency medicine residents used direct laryngoscopy versus video laryngoscopy for emergency department intubation. In this study the authors concluded that use of video laryngoscopy resulted in “significantly fewer” esophageal intubations in this setting and recommended that emergency medicine residency training programs should consider using video laryngoscopy for all intubations, a position they advocate especially strongly for patients suspected of having a difficult airway [66].

From: Sakles JC, Mosier J, Patanwala AE, Dicken J. Learning curves for direct laryngoscopy and GlideScope® video laryngoscopy in an emergency medicine residency. West J Emerg Med. 2014 Nov;15(7):930-7. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.9.23691. Epub 2014 Oct 29. PubMed PMID: 25493156; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4251257.

Copyright ©2014 Sakles et al. From an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Non-Commercial Attribution License, which permits its use in any digital medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not altered.

It also appears that the specific type of videolaryngoscope used may be relatively unimportant in emergency department intubation success. Mosier et al. [67] reviewed 463 intubations (230 with the GlideScope and 233 with the Storz C-MAC) and found that both yielded similar success rates.

The GlideScope experience in the ICU setting is somewhat similar. Ural et al. [68] compared intubation before and after acquisition of a GlideScope dedicated to ICU use and found that it did not lead to an “immediate reduction in attempts at orotracheal intubation” or to a reduction in complication rates. By contrast, Kory at al [69]. studied 138 urgent ICU endotracheal intubations carried out by pulmonary and critical care medicine fellows, and found that use of videolaryngoscopy “improved intubation success and decreased complications” compared to direct laryngoscopy. The authors suggested that videolaryngoscopy should be used “when urgent intubations are performed by less experienced operators.”

In a similar ICU study by Silverberg et al. [70] involving pulmonary and critical care medicine fellows, patients urgently in need of intubation were randomized to use of the GlideScope video laryngoscopy or to direct laryngoscopy. Success on the first attempt was achieved in 74% of the GlideScope patients group compared with only 40% amongst the direct laryngoscopy patients.

In the prehospital arena, a number of studies have demonstrated the value of videolaryngoscopy. Bjoernsen and Lindsay [71] opined that while “direct laryngoscopy always should be retained as a primary skill …. the video laryngoscope has the potential to be a good primary choice for the patient with potential cervical spine injuries or limited jaw or spine mobility, and in the difficult-to-access patient.” Struck et al. [72] conducted a retrospective observational study of their helicopter rescue program and concluded that the GlideScope “may be a valuable support instrument in the prehospital management of difficult airways in emergency patients.”

However, not all prehospital studies of the GlideScope have been favorable. In a study by Trimmel et al. [73], prehospital GlideScope use was associated with impaired visualization of the monitor because of ambient light, thus resulting in a lower intubation success rate when compared with direct laryngoscopy (61.9% versus 96.2%.)

10. GLIDESCOPE USE IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

The GlideScope can also be used in neonates and pediatric patients. Trevisanuto et al. [74] described their initial experience with GS use in five neonates and outlined the difficulties encountered. Kim et al. [75] compared the use of the GlideScope with direct laryngoscopy in 203 children. The view of the glottis was scored (Cormack and Lehane (C&L) grade) with and without BURP (backward, upward and right-sided pressure) [76] in both instances. The GlideScope improved the view without BURP in the patients with C&L grade 2 (16/26) and with C&L grades 3 and 4 (7/11). The view with BURP was also improved by the GlideScope in C&L grade 2 (4/9) and with C&L grades 3 and 4 (4/5). The average time for intubation was 36.0 s in the GS group and 23.8 s in the DL group. The authors concluded that “in children, the GlideScope provided a laryngoscopic view equal to or better than that of direct laryngoscopy but required a longer time for intubation.”

Lee et al. [77] evaluated the usefulness of the GS for improving the laryngoscopic view in 23 pediatric patients whose Cormack and Lehane grade under direct laryngoscopy was 3 or 4 and concluded that a Glidescope one size smaller than the usual blade based on weight “significantly improved the laryngoscopic view” when compared with DL or with the GS blade based on weight.

Finally, Vadi et al. [78] compared trainee intubation times obtained using the GlideScope Cobalt VL, the Storz DCI VL and DL in young children with immobilized cervical spines and concluded that VL “may enhance best Cormack-Lehane glottic view during manual in-line cervical spine immobilization, but additional technical skills are needed to successfully complete tracheal intubation” and that “obtaining a grade 1 Cormack-Lehane glottic view was less likely” with DL.

11. CERVICAL SPINE MOVEMENT

A number of investigators have studied the question as to the best airway management technique in the patient with suspected cervical spine injury, since in patients with possible cervical spine injury movement head and neck should be minimized [79, 80].

Turkstra et al. [81] used fluoroscopy to study 36 normal adult patients immobilized with in-line stabilization in a crossover trial of either Trachlight (Intubating Lighted Stylet) or GlideScope intubation to DL. While cervical spine motion using the GS was reduced 50% as compared to DL at the C2-5 segment, no difference was found at the other segments studied. As with other studies, GS laryngoscopy took significantly longer than with DL. The authors found that the best results were obtained using a Trachlight. (More information on Trachlight intubation is available in a comprehensive review by Agro et al. [82]).

Robitaille et al. [83] similarly compared cervical spine motion during GS vs DL intubation in 20 patients using continuous fluoroscopy. Manual in-line stabilization of the head was performed. Although no significant difference in average segmental spine movement was found at any segmental level, glottic visualization was “significantly better” with GS use.

Wong et al. [84] studied cervical spine motion during flexible bronchoscopy as compared with the GS when no cervical immobilization was used, hypothesizing that the GS would not cause significantly greater cervical spine movement than fibreoptic bronchoscopy. To study this matter, 28 adults without cervical disease requiring intubation for radiographic procedures were randomized to either the GS or the flexible bronchoscope (FB), with continuous fluoroscopy used to assess cervical spine movement during intubation. Cervical spine movement was compared both during laryngoscopy and with tongue pull and jaw thrust maneuvers. The authors found that use of the GS during intubation under general anesthesia resulted in greater cervical movement than FB, and that the jaw thrust maneuver, often used to facilitate FB, also resulted in cervical spine movement.

Kill et al. [85] studied cervical spine movement in patients with an unsecured cervical spine, comparing conventional DL with use of the GS in 60 anesthetized patients. Using video motion analysis taken with a lateral view, the maximum extension angle was measured with reference to standardized anatomical points. The authors found that Intubation by physicians with some experience in videolaryngoscopy was associated with a reduced angle deviation compared to inexperienced physicians. As with other studies, GS intubation time (median 24 s) exceeded the time needed for DL (53 s). In 3 patients randomized to DL where intubation by DL failed, intubation was successful following GS use. The authors concluded that “GlideScope videolaryngoscopy reduces movements of the cervical spine in patients with unsecured cervical spines and therefore might reduce the risk of secondary damage during emergency intubation of patients with cervical spine trauma.”

12. GS USE AS AN ADJUNCT TO FOB

The GS can also be useful in some cases of difficult fibreoptic intubation [86]. Here, the GS is introduced in the usual manner, followed by introduction of the fibreoptic bronchoscope. Such an arrangement provides simultaneous ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ views that can be particularly helpful. In the teaching setting, the instructor is able to use the video laryngoscopy device to see the tip of the bronchoscope as controlled by the student, so the instructor can provide real-time guidance to supplement the view provided by the bronchoscope. When used for purely clinical purposes, the GS can assist in a fiberoptic intubation by providing an alternative view of the airway; such a view can be helpful, for example, in the case of a bloody airway or severely distorted anatomy. Also, should the tracheal tube get caught on the arytenoids or other laryngeal structures, it becomes evident on the GS display, and appropriate corrective action (such as twisting the tube) can easily be taken. Also note that the procedure can be performed either awake or under general anesthesia depending on the clinical circumstances.

13. GLIDESCOPE-ASSISTED NERVE INTEGRITY MONITORING (NIM) TUBE PLACEMENT

The Nerve Integrity Monitoring (NIM) tube is often used for intra-operative recurrent laryngeal nerve monitoring during thyroid and parathyroid surgery [87, 88]. Positioning of this special tube with its embedded electrodes to the correct depth is critically important [89]. This positioning is most easily achieved using the GS, as it allows both the anesthesiologist and the surgical team to witness correct placement of the NIM tube with outstanding clarity [90-92].

14. GLIDESCOPE-ASSISTED PLACEMENT OF NASOTRACHEAL TUBES

In addition to facilitating orotracheal intubation, the GS can be useful for the placement of nasotracheal tubes [93-99]. Unlike that case when DL is used, Magill forceps are not employed; instead, to position the tube into the glottis one uses a combination of rotating the tube, flexion of the patient's neck and /or minimal rotation of the patient's head. Jones et al. [94] offer the following additional tip: once the tube tip of has entered the vocal cords, it is often helpful to reduce the distraction of the anterior neck tissues by lowering the GS, advancing the tube into the trachea, and then lifting the GS back up to ensure the tube is still between the vocal cords.

An important reason that Magill forceps are not employed with GS-assisted placement of nasotracheal tubes is that the design of the forceps is optimized for use with DL. Boedeker has developed a curved forceps design optimized for videolaryngoscopy [100]; the curve of these forceps “allows both the tip of the forceps and the glottic opening to be simultaneously visible in the field of view during videolaryngoscopy” making them suitable for both nasotracheal tube positioning as well as for the removal of glottic foreign bodies.

Galgon and Ketzler [101] have described how the GS might be used to assist in the conversion from a nasotracheal tube to an orotracheal tube in a patient with a known difficult airway. The technique used was described as follows:

The GlideScope videolaryngoscope was inserted, achieving a full view of the glottic inlet with the nasotracheal tube in situ. An endotracheal tube (ETT) loaded on a GlideRite Rigid Stylet was advanced through the oropharynx into view. Advancement of this ETT to the glottic opening was tested and achieved. With both tracheal tubes in view, the nasotracheal tube cuff was deflated and withdrawn from the glottic opening. While maintaining videoscopic visualization, the orotracheal tube was advanced through the vocal cords into the trachea.

A similar approach can be used to assist in the conversion from an orotracheal tube to a nasotracheal tube [102-104].

15. GLIDESCOPE-ASSISTED PLACEMENT OF DOUBLE-LUMEN TRACHEAL TUBES

The GS has proven to be useful in a number of cases where Double-Lumen Tube (DLT) placement was expected or proved to be difficult by DL [105]. A case report by Hernandez and Wong [106] offers some suggestions for left DLT placement using the GS:

We suggest bending the stylet of the DLT so that the distal 16 to 20 cm of the DLT curve follows the curve of the Glidescope, and the other end of the DLT angles out to the right side. After the bronchial cuff passes through the VC, withdraw the stylet of the DLT about 2 cm. Then, rotate the DLT 90° counterclock-wise while advancing the DLT to the desired depth.

Other reports on the use of the GS with DLTs have been provided by other authors [107-109]. Onrubia et al. [109] describe a case of GlideScope-assisted awake DLT insertion under topical anesthesia in a patient known to be difficult to intubate. Bussieres et al. [110] have described a special stylet specifically designed for use of the GlideScope® with insertion of DLTs.

16. GLIDESCOPE-ASSISTED RETRIEVAL OF FOREIGN BODIES FROM THE AIRWAY

The GlideScope can be a useful adjunct in attempting to retrieve foreign bodies from the airway. The use of the GS in the removal of foreign bodies impacted at the hypopharyngeal level has been described by several authors [111-115]. The use of the GS in the removal of intratracheal foreign bodies has also been described [116]. An important potential advantage of using the GS in the case of hypopharyngeal foreign bodies is the fact that general anesthesia can often be avoided, using only conscious sedation in conjunction with topical anesthesia, while the greatly magnified view provided by the GS “represents a great improvement in identifying and removing ... even small and thin foreign bodies not recognized by radiological and otolaryngology examination and not readily detected by direct endoscopy” [115].

17. GLIDESCOPE-ASSISTED PLACEMENT OF NASOGASTRIC TUBES

Given that intraoperative nasogastric tube (NGT) insertion is often difficult, a number of techniques to facilitate this procedure have been described (e.g., [117-119]). Lai et al. [120] suggested that the insertion of NGTs could be facilitated in intubated patients using the GlideScope as follows:

The blade of the GlideScope® was inserted first into the patient's mouth to get the views of the pharyngeal and laryngeal area then the nasogastric tube was inserted via the nostril with lubrication until it reached the pharyngeal area. After that, the cuff of the tracheal tube was released and the nasogastric tube was advanced gently with the patient's chin lifted.

Moharari et al. [121] conducted an 80 patient clinical trial of NGT placement by the above means, employing random allocation to traditional (blind) NGT insertion or to insertion with the assistance of a GlideScope. NGT placement was not successful within 3 attempts in 4 of the control group patients and in 1 patient in the GlideScope group. The mean insertion time in the GlideScope group was 27.7 s shorter than in the control group, while complications such as pharyngeal bleeding or mucosal injury were reported in 14 patients of the control group but only 8 patients in the GlideScope group.

18. LEARNING CURVES FOR USING THE GLIDESCOPE

It is commonly believed that mastering tracheal intubation using a GlideScope is easier than via direct laryngoscopy. As noted earlier, Healy et al. [16] compared the GlideScope, CMAC, and Storz DCI with the Macintosh laryngoscope during simulated manikin difficult laryngoscopy and found that all three of the methods of video laryngoscopy were superior to use of the Macintosh laryngoscope Fig. (5). Similar results were obtained in studies of emergency medicine residents, discussed in the earlier section on emergency airway management outside of the operating room.

However, this finding may not apply to infant laryngoscopy. In a study by Faden et al. [122] the authors studied 16 anesthesiology residents who had no prior experience with infant airway management. The participants each performed 10 tracheal intubations (5 GlideScope® Cobalt Video Laryngoscope (GCV) and 5 direct laryngoscopes, randomized) in infants weighing 10 kg or less. The time to optimum view of the vocal cords and the time needed for tracheal intubation were both recorded. The authors concluded that the learning curve for infant

Cortellazzi et al. [123] studied the performance of nine trainees during 890 intubations, with an additional 72 intubations performed by expert anesthetists serving as a control group. The author defined expertise in videolaryngoscopy as achieving a 90% probability of optimal performance, consisting of a single laryngoscope insertion and obtaining a Cormack and Lehane grade-1 view, it was found that with these criteria expertise required 76 attempts, suggesting that “expertise in videolaryngoscopy requires prolonged training and practice.” GlideScope® laryngoscopy and intubation by novice residents is “flat and identical to that with direct laryngoscopy” and that their results “support the notion of teaching the use of the infant GCV to junior anesthesiology residents.”

19. COMPLICATIONS ASSOCIATED WITH THE GLIDESCOPE

Perforation of the palatopharyngeal arch or soft palate is a rare but potentially important complication associated with use of the video laryngoscopy [124-130]. Other types complications have also been reported: Magboul and Joel [131] described a possible lingual nerve injury from the Gliderite rigid stylet used in conjunction with the GS.

To avoid such injuries, the following four-step technique is suggested when using the GS [132]:

- The GlideScope® is first introduced into the midline of the oral pharynx with the left hand.

- The epiglottis is identified on the screen and the scope is manipulated to obtain the best glottic view.

- The endotracheal tube is then guided into position near the tip of the laryngoscope by direct vision.

- When the distal tip of the endotracheal tube disappears from direct view, it should be viewed on the monitor. Gently rotate or angle the tube to redirect as needed.

Weissbrod and Merati [133] have further suggested that such complications might be eliminated by using the GS in conjunction with a flexible bronchoscope acting as a “smart” stylet. In such case the bronchoscope is not used for its imaging capacity, but instead used as a “manipulatable stylet for the endotracheal tube”.

20. THE LARYGOSCOPY DEBATE

For many individuals in the airway community a debate has arisen as to the appropriate role of the GS in clinical airway management [134-136]. One question is whether medical students and residents should be taught the use of the GS before being taught DL, the arguments in favor of this approach is that the teacher sees exactly what is happening when the GS is in use and, additionally, the excellent view provided by the GS familiarizes the learner with the glottic structures in a manner that helps with the learning of DL. Complicating this issue is the availability of the GlideScope Direct, a videolaryngoscope specifically designed to assist with the teaching of DL [137].

Another debate is whether clinicians who intubate only occasionally (e.g., paramedics) might best serve their patients by being trained only on use of the GS, especially because of the abundant literature supporting the notion that learning GS use is easier than learning DL [138]. Cooper [139] provides the following commentary in these and related airway issues:

DL is a legacy technique; it was introduced at a time when there were no alternatives. We now have a wealth of supraglottic airway devices and are able to safely avoid tracheal intubation in a significant number of patients. But when tracheal intubation is deemed appropriate, fiberoptic and video technology can generally provide a laryngeal view, even in patients in whom this was previously presumed to be difficult or impossible. Our current airway assessment is predicated on DL. An anticipated difficult DL does not mean that laryngoscopy will be difficult if DL is not employed and we should not reserve the best methods for only our most difficult patients; they should be offered to all our patients. This will provide our patients with the best care. It will ensure that we gain experience with the techniques we select and an appreciation of their limitations and value.

CONCLUSION

The GlideScope video laryngoscope, by virtue of providing a glottic view superior to direct laryngoscopy, has had a profound impact on clinical airway management and airway safety. That said, mastering the use of the GlideScope and other videolaryngoscopes requires knowledge of a number of special tips and tricks to ensure success. These include the need for a stylet or airway guide as well as a need to remember that a deliberately restricted laryngeal view with the GlideScope provides better intubation results compared with a full glottic view.

Finally, one should always bear in mind that a failure to heed standard usage methods can result in complications such as perforation of the palatopharyngeal arch or soft palate as well as lead to other types of complications. Always remember that insertion of the GlideScope and endotracheal tube should begin under direct vision – only when the distal tip of the endotracheal tube disappears from direct view should one’s attention then be directed to the video display.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| BURP | = backward upward and right-sided pressure |

| C&L | = Cormack and Lehane (view at laryngoscopy) |

| DL | = direct laryngoscopy |

| ETT | = endotracheal tube |

| FB | = flexible bronchoscope |

| FOB | = fiberoptic bronchoscopy GS GlideScope video laryngoscope |

| N | = Newtons (unit of force) |

| NGT | = nasogastric tube |

| NIM | = nerve integrity monitoring |

| S | = Seconds (unit of time) |

DISCLOSURE

Part of this article has been previously posted at “glidescope.homestead.com”

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.