All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Chewing Gum Use in the Perioperative Period

Abstract

A synopsis of the latest research on the perioperative use of chewing gum by surgical patients is presented, focusing on the preoperative and postoperative periods. Current data now suggest that the preoperative use of chewing gum does not adversely affect gastric emptying and that the postoperative use of chewing gum may actually aid recovery from some forms of major surgery. Additionally, the use of chewing gum may increase alertness and serve to reduce stress, as well as offer important oral health benefits.

1. INTRODUCTION

Commercialization of chewing gum took place around 170 years ago. This brief review presents a synopsis of the latest research on the use of chewing gum by surgical patients, focusing on the preoperative and postoperative periods. It appears that the preoperative use of chewing gum does not adversely affect gastric emptying and that the postoperative use of chewing gum may actually aid bowel recovery following some forms of major surgery.

2. PREVENTION OF GASTRIC ASPIRATION

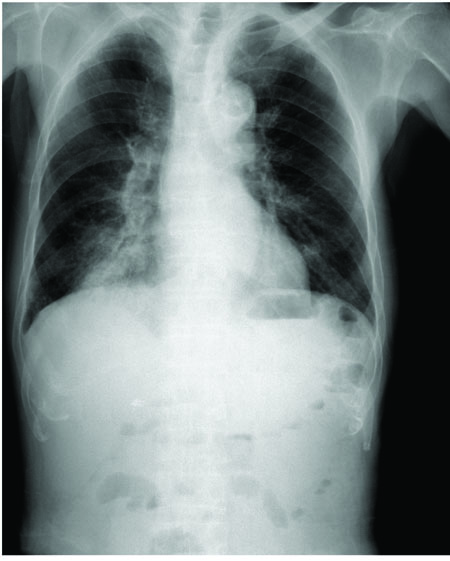

One major concern of all anesthesiologists is the possibility that their patients may aspirate gastric contents during general anesthesia. This is because several pulmonary syndromes may occur following aspiration, depending on the amount and nature of the aspirated material, the host's immune response to the aspirated material and other factors [1]. Perhaps, the best known of these syndromes are aspiration pneumonitis (Mendelson's syndrome in Fig. (1)), which is principally a chemical injury to the lung parenchyma, and aspiration pneumonia, which is an infectious process related the inhalation of oropharyngeal secretions rich in pathogenic bacteria. In a study of medical malpractice cases resulting from aspiration, Eltorai et al. [2] found that the most common alleged malpractice did not secure the airway with an endotracheal tube when faced with an elevated aspiration risk, and with “failure to perform a proper rapid-sequence induction and/or place a nasogastric tube” for the purposes of gastric decompression prior to the induction of anesthesia.

| Type of Meal | Minimum Fasting Interval |

|---|---|

| Clear fluids (e.g., water, apple juice, hot black tea, oral medications with a sip of water) | 2 hours |

| Human breast milk | 4 hours |

| Infant formula | 6 hours |

| Non-human milk (e.g., cow’s milk) | 6 hours |

| Light meal (e.g., tea and toast, broth, apple sauce) | 6 hours |

| Meals rich in fatty or fried components (e.g., cheese burger with fries and onion rings) |

8 hours |

3. PREOPERATIVE CHEWING GUM AND GASTRIC EMPTYING

One concern related to gastric aspiration sometimes raised is that allowing patients to chew gum in the preoperative fasting period increases gastric secretions, thereby theoretically increasing the risk of aspirationi. While perioperative fasting guidelines from the ASA [3] (Table 1) and other agencies are helpful in guiding the management of patients through the perioperative period, experts still differ widely in their recommendations concerning the use of chewing gum in the preoperative period, with some past experts recommending delaying the surgery and others who would allow it to proceed on the basis of recent research findings such as those discussed next.

In a bedside gastric ultrasoundii study by Valencia et al. [4], 55 healthy volunteers chewed gum for an hour, with gastric volumes assessed by ultrasonography at baseline and then hourly. The investigators found that “the proportion of subjects who presented a completely empty stomach (Grade 0 antrum) was similar at baseline and after 1 h of gum-chewing [81% vs. 84%, p = 0.19, CI 95% (-12%, 16%)]” and that “among those subjects who had visible fluid at baseline, the volume remained unchanged throughout the study period.”

In another ultrasound-based study by Bouvet et al. [5], the authors carried out a randomized crossover trial on 20 healthy volunteers. Each crossover session started with an ultrasound antral assessment, followed by drinking 250 ml of water. The subjects then either chewed a sugared gum for 45 min or did not (control group). The half-time to gastric emptying, the total gastric emptying time, and other measurements were taken via ultrasonography. The authors concluded that “chewing gum does not affect gastric emptying of water and does not change gastric fluid volume measured 2 h after ingestion of water.”

In a study by Dubin et al. [6], 77 patients were randomly assigned to get sugarless gum or to serve as a control subject. On the basis of their findings, the authors concluded that surgery need not be delayed if a patient arrives in the OR chewing sugarless gum.

Ouanes et al. [7] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 287 patients to determine whether preoperative gum chewing affects gastric pH and gastric fluid volume. They found that “the presence of chewing gum was associated with small but statistically significant increases in gastric fluid volume” but that changes in gastric pH were not found. The authors concluded that “elective surgery should not necessarily be canceled or delayed in healthy patients who accidentally chew gum preoperatively.”

Finally, Poulton [8] found “no evidence that gum chewing during pre-anesthetic fasting increases the volume or acidity of gastric juice in a manner that increases risk” but instead suggested that preoperative gum chewing may be beneficial in that “gum chewing promotes gastrointestinal motility and physiologic gastric emptying.” His recommendation is that “gum chewing should cease when sedatives are given and all patients should be instructed to remove any chewing gum from the mouth immediately prior to anesthetic induction.” The last part of this recommendation is nicely reinforced by several case reports of chewing gum contributing to airway misadventures [9-11].

4. POSTOPERATIVE CHEWING GUM TO IMPROVE BOWEL FUNCTION

Ertas et al. [12] studied whether gum chewing influences the return of bowel function after gynecologic staging surgery. Patients undergoing complete staging surgery for gynecological malignancies were randomly assigned either to repeated gum-chewing (n = 74) or to a control group (n = 75). The authors found that the time to flatus, time to defecation, time to tolerate diet and length of hospital stay were on average “significantly reduced in patients that chewed gum compared with controls.” Additionally, ileus symptoms were less frequent in the gum-chewing group. The authors concluded that early postoperative gum chewing after “elective total abdominal hysterectomy and systematic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy hasten the time to bowel motility and the ability to tolerate feedings” and that this treatment is sufficiently effective that it “should be added as an adjunct in postoperative care of gynecologic oncology”.

Vásquez et al. [13] performed a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (6 trials/244 patients) to better understand the effect of gum chewing on ileus after colorectal surgery. The authors concluded that in patients suffering from ileus after colonic surgery, “gum chewing in addition to standard treatment significantly reduces the time to first flatus and the time to first passage of feces when compared to standard treatment alone” and advocated for gum chewing being added to the routine management of these patients.

5. CHEWING GUM FOR THE TREATMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Darvall et al. [14] conducted a pilot study of 94 female patients undergoing laparoscopic or breast surgery. Patients experiencing Postoperative Nausea or Vomiting (PONV) in the Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU) received either ondansetron 4 mg i.v. or chewing gum. It was found that chewing gum was “not inferior” to ondansetron to relieving PONV in this setting.

6. CHEWING GUM FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF STRESS

There is even evidence that chewing gum may play a role in relieving stress [15] as well as in increasing alertness [16-18] and in increasing memory performance [19]. One proposed mechanism for these findings is that increased activity in the Locus coeruleus may be involved [20].

7. CHEWING GUM FOR ORAL HEALTH

The oral health benefits of chewing gum are sometimes unappreciated. Dodds [21] points out that not only does the use of sugar-free gum provide a valuable anti-caries benefit but that chewing sugar-free gum promotes saliva production, thereby providing dental benefits such as the rapid oral clearance of sugars, the neutralization of plaque pH after a sugar challenge, and remineralization of early dental lesions.

CONCLUSION

Data now exist to show that the preoperative use of chewing gum does not adversely affect gastric emptying. Also, the postoperative use of chewing gum may aid bowel function recovery after some forms of major surgery. Finally, the use of chewing gum may increase alertness and serve to reduce stress, as well as offer oral health benefits.

NOTES

i See, for instance, http://www.northsideanesthesiology.com/faqs.php#Why can't I eat or drink anything before surgery? and http://www.anesthesia-resources.com/ why-can-t-i-eat-or-chew-gum-before-surgery-.html

ii For an introduction to gastric ultrasound, visit http://www.gastricultrasound.org/

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.